Three lines of defence: a panacea?

AXVECO performed a short survey among Dutch Financial Institutions to establish whether the three lines of defence model was still viewed as valid and identify implementation challenges.

We received a large number of responses (62) from senior risk managers. 40% of respondents represented the banking sector, 24% insurance, 12% asset managers and 24% other (including consultants and regulators). The results are presented in this paper, combined with our knowledge and experience from interactions with senior business stakeholders.

Risk governance and the three lines of defence model

Risk Governance can be defined as the subset of corporate governance decisions and actions that ensure effective risk management, including organisational structures, policies, processes and decision-making within the area of risk. Article 22 of the European Capital Requirement Directives (CRD 2006/48/EC)[i] requires, that every credit institution has robust governance arrangements, which include a clear organisational structure with well defined, transparent and consistent lines of responsibility, effective processes to identify, manage, monitor and report the risks it is or might be exposed to, adequate internal control mechanisms, including sound administrative and accounting procedures, and remuneration policies and practices that are consistent with and promote sound and effective risk management‟.

The most important reference work in the field of Risk Governance is the European Banking Association’s (EBA) “Guidelines on Internal Governance (GL 44)” [ii]. These guidelines have been issued by the EBA after a survey conducted in 2009 by the Committee of European Banking Supervisors on the implementation by supervisory authorities and institutions of its Internal Governance Guidelines in response to the issues highlighted by the financial crisis[iii].

| The three lines of defence model is accepted by the Financial Services industry as a sound practice. |

Risk Governance is the responsibility of the governing bodies of senior management and the Board, who should play an active role in setting the organisation’s objectives and establishing governance structures and processes to manage the risks in achieving the objectives. Organisations should put in place a structure of risk responsibilities throughout the organisation, as a result of which, everybody in the organisation will become aware of their own risk responsibilities and accountabilities and those of others with whom they work.

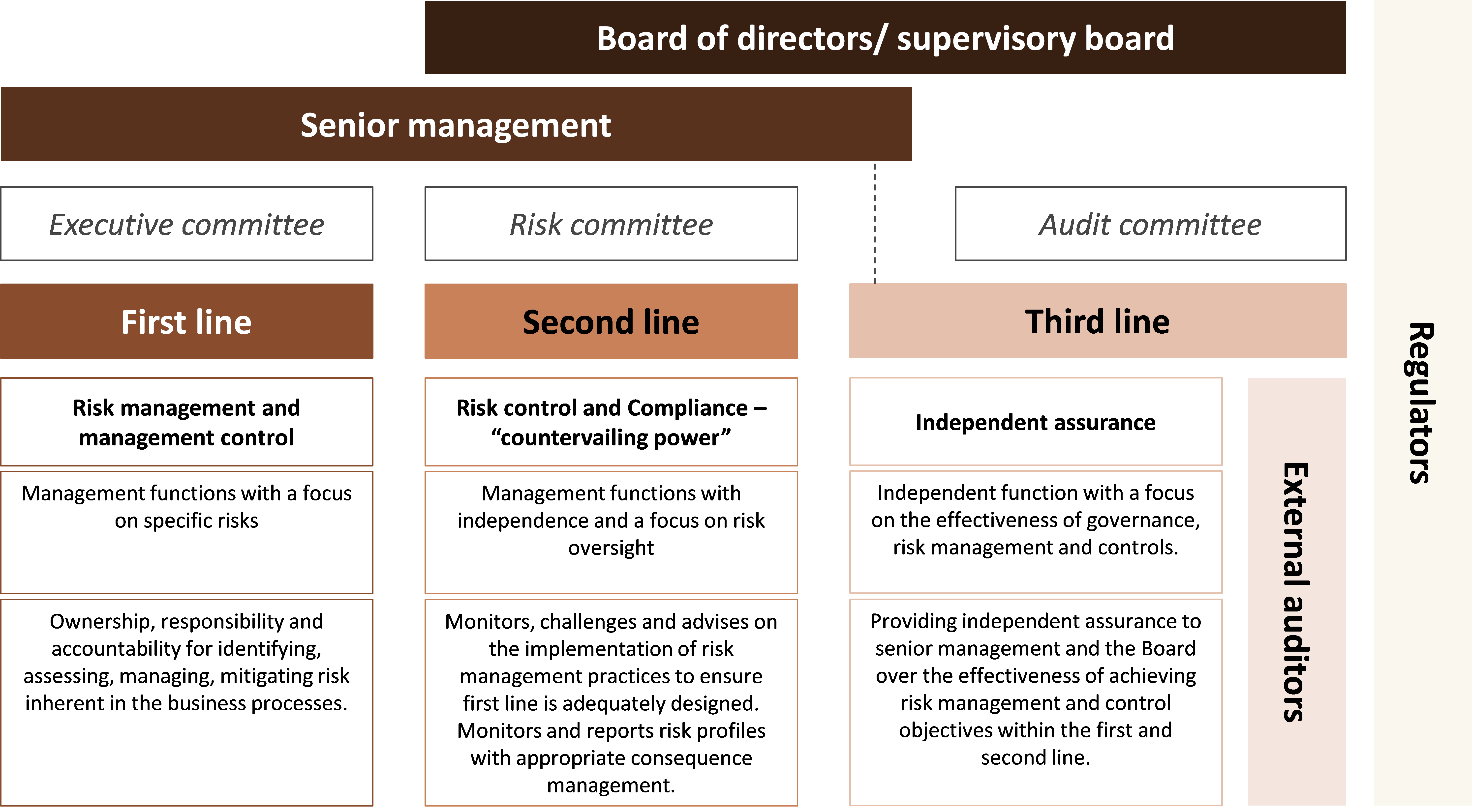

The EBA GL 44 guidelines, applied by the Dutch National Bank when reviewing governance structures, are consistent with the well-known three lines of defence model. This is a simple model, with each “line” playing a critical role in the governance of the risks the organisation is facing (see figure 1):

- First line: refers to the management functions that own and manage risk and controls under the supervision of the executive committee;

- Second line: refers to the management functions that perform risk control and compliance oversight with limited independence. They challenge and advise the first line and serve as a countervailing power. A Risk Committee, chaired by a non-executive director, oversees the implementation of risk policies across the organisation;

- Third line: generally refers to Internal and External Audit who provide independent assurance over frameworks, processes and controls to an independent Audit Committee, which comprises entirely of non-executive directors; and

- Regulators: within the Financial Services industry regulators can be considered as an additional line of defence providing oversight on behalf of external stakeholders and setting risk management and control standards and requirements for the players in the industry.

Figure 1: Generic articulation of the three lines of defence

The three lines of defence model remains valid, but is highly dependent upon implementation at all levels

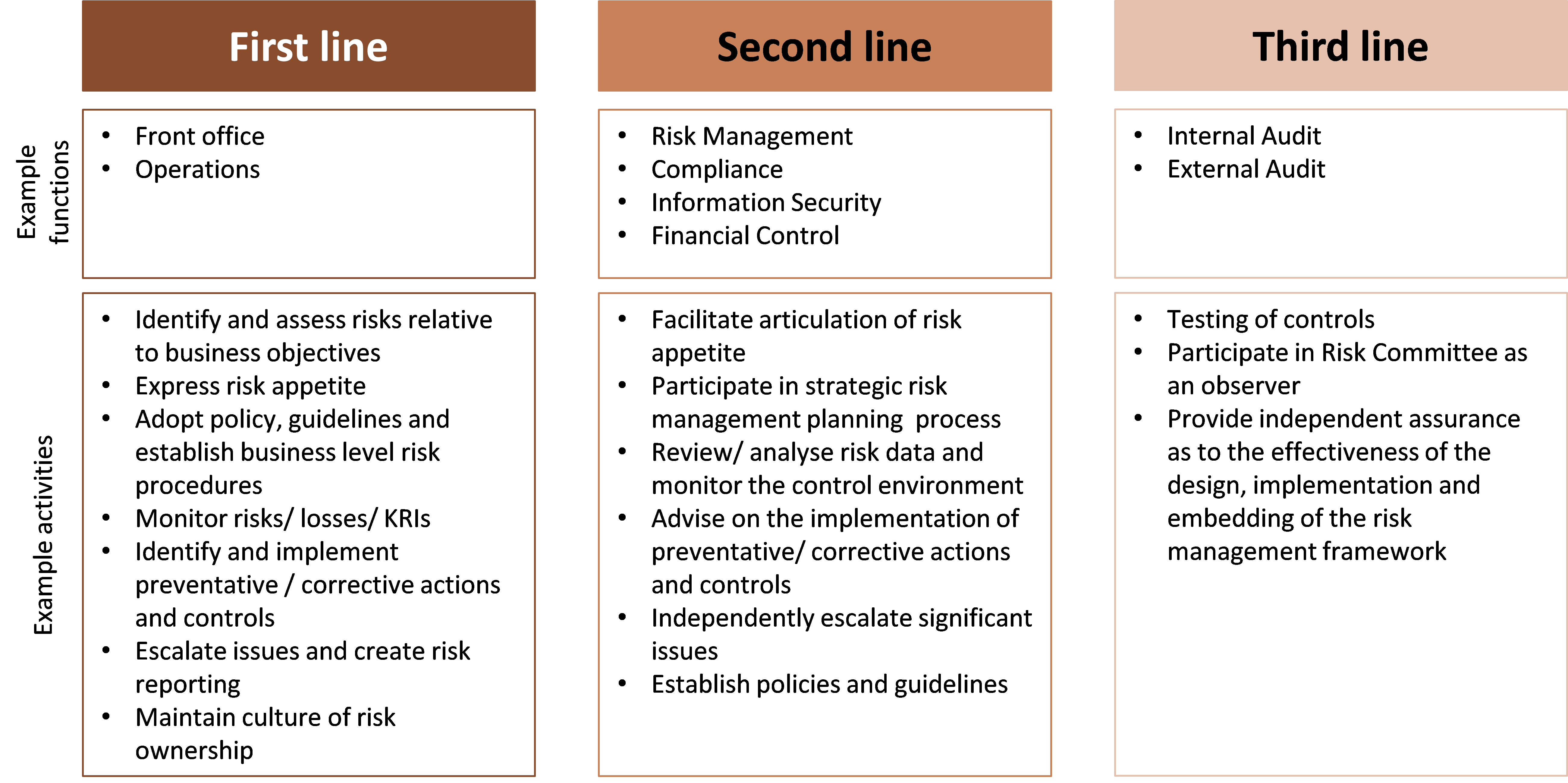

The three lines of defence model describes how specific duties related to risk and control could be assigned and coordinated within an organisation. An effective model will help an organisation to achieve its objectives with effective management of risk. Therefore, on paper the model remains valid and all three lines of defence (in some form) should exist in all organisations. Our survey shows that all FS organisations do indeed adopt some form of the model. See figure 2 for example functions and activities across the lines. So far so good.

In practice, however, the model has attracted significant criticism. It has been accused of becoming a box-ticking exercise promoting a ‘misplaced sense of security’. Following numerous, recent major incidents (internal fraud, excessive risk taking, material misstatements or misconduct), the effectiveness of the three lines of defence model has been called into question. This in turn raises questions about whether additional efforts are needed to fully embed the underlying philosophy.

Figure 2: Example functions and activities across the lines of defence

| The problem lies more in the implementation and operation of the model than the design of the model itself. |

In our opinion, the key problem lies more in the implementation and operation of the model, rather than the design of the model itself. We have identified five inhibitors to a successful implementation or operation of the three lines of defence. Each inhibitor in itself will compromise the effectiveness of the model. In reality, for most organisations a combination of these inhibitors is present.

- Ambiguous responsibilities. Despite the apparent simplicity of the three lines of defence model and the need for clear governance and organisation, there is often considerable contention and confusion around responsibility for key activities. If this happens, responsibilities may become blurred and the careful balance between the management, monitoring and assurance functions misaligned, leading to a breakdown of control. See exhibit 1 for survey findings highlighting discrepancies in the allocation of activities across the three lines of defence model.

- Lack of first line accountability. The respondents to our survey indicate that the first line remains most important, whilst it is also seen as being the least effective. The main challenge raised by the survey respondents is that implementation of the model within their organisations allows for ambiguity around roles and responsibilities. Where this happens, the first line can neglect their risk management duties, which typically forces the second line to step in and address this weakness. This can result in the risk function owning risks or performing first line tasks such as process documentation.

- Lines operating in silos. The lines of defence should be separate to allow for effective management, monitoring and assurance, but they should not operate in silos. There should be a shared understanding of risk and controls and no gaps in the coverage of any risks. Management and monitoring functions should be talking the same risk language and leverage a common infrastructure and methodology. Information should be shared to ‘connect the dots’ across risk categories and to identify exploitation of control weaknesses. The survey reveals that the major area for contention is the allocation of second line tasks. In Exhibit 2 we have illustrated three generic organisational models that we see in the industry for the second line to ensure cooperation is achieved (See exhibit 2).

- Lack of countervailing power. A lack of authority, objectivity and a critical mindset in combination with poor business and communication skills often leads to professionals within the second line operating without sufficient stature, credibility or lacking the willingness to speak up when needed. This heavily undermines the countervailing power of the second line of defence, which is intended to oversee that the processes and controls implemented by the first line are designed and operating effectively. In the current increasingly complex regulatory and business environment, the first line needs, and governing bodies expect, the risk and compliance functions to be the countervailing power.

- Static model within a dynamic environment. Risk Governance and the organisational structure require alignment with the (changing!) business model. The fulfilment of the roles within each line of defence should fit the needs of the organisation, which may change over time. New risks may emerge, requiring new competences, expertise, processes and tools. For example when a new ‘App’ based service leads to higher technical support and reduced human support of customer interaction, the nature and profile of the risks of the business area will change requiring a change in the way the risks are identified and managed.

The implementation of the three lines of defence requires a mix of hard and soft controls

The five implementation inhibitors described above do not invalidate the model itself, but undermine its implementation in practice. The Pavlov reaction within many organisations when fixing a control breakdown or remediating a large incident is to invest in hard controls: clarify organisational models, roles and responsibilities, enhance risk management frameworks, processes, instruments, methodologies and controls with more documentation of policies and procedures. For example, organisations should ensure that enhanced cooperation exists between the individual risk functions within the second line of defence (Financial Risk Management, Enterprise-wide Risk Management, Operational Risk Management, Information Security and Compliance) and with the other business functions such as Human Resources and Information Technology as well as across the other lines, to address the silo mentality.

In many cases, the maturity of such hard controls needs enhancing, but this cannot be the whole answer to fully resolve the implementation challenges. The hard controls will only be effective when operating in combination with soft controls since Risk Governance is fundamentally linked to an organisation’s self-awareness of its balance between risk-taking and control. Risk Governance should a belief, a way of thinking and embedded within the organisation’s DNA through soft controls such as core values, risk culture, involvement, empowerment, transparency and tone at the top.

| Risk Governance requires a balance between control and trust. |

Effective Risk Governance can only be implemented with active support and guidance of the organisation’s Senior Management and Board. They set the context for establishing the best governance structure to manage the risks within the organisation and they should be explicit in articulating their appetite for risk in the achievement of the organisation’s objective. They should ruthlessly hold the first line of defence accountable for the management of risks and controls and align incentives and remuneration with these accountabilities.

Further, they should give the second line sufficient mandate that empowers them and obtain the authority to advice and challenge the first line when needed. We see a desire to move away from the second line in a “police men” role towards an effective and credible countervailing power. IN our opinion, this require a new type of professional within the second line; namely, one that understands the business holistically (strategy, finance, operations and risk), has strong relationship building and communication skills.

Finally, Business environments are becoming increasingly complex with the transition to digitised service delivery, raising concerns around integrity and misconduct, and evolving sophistication in financial crime. Achieving effective Risk Governance is a continuous process within a dynamic environment that includes a review of the three lines of defence model on a regular basis.

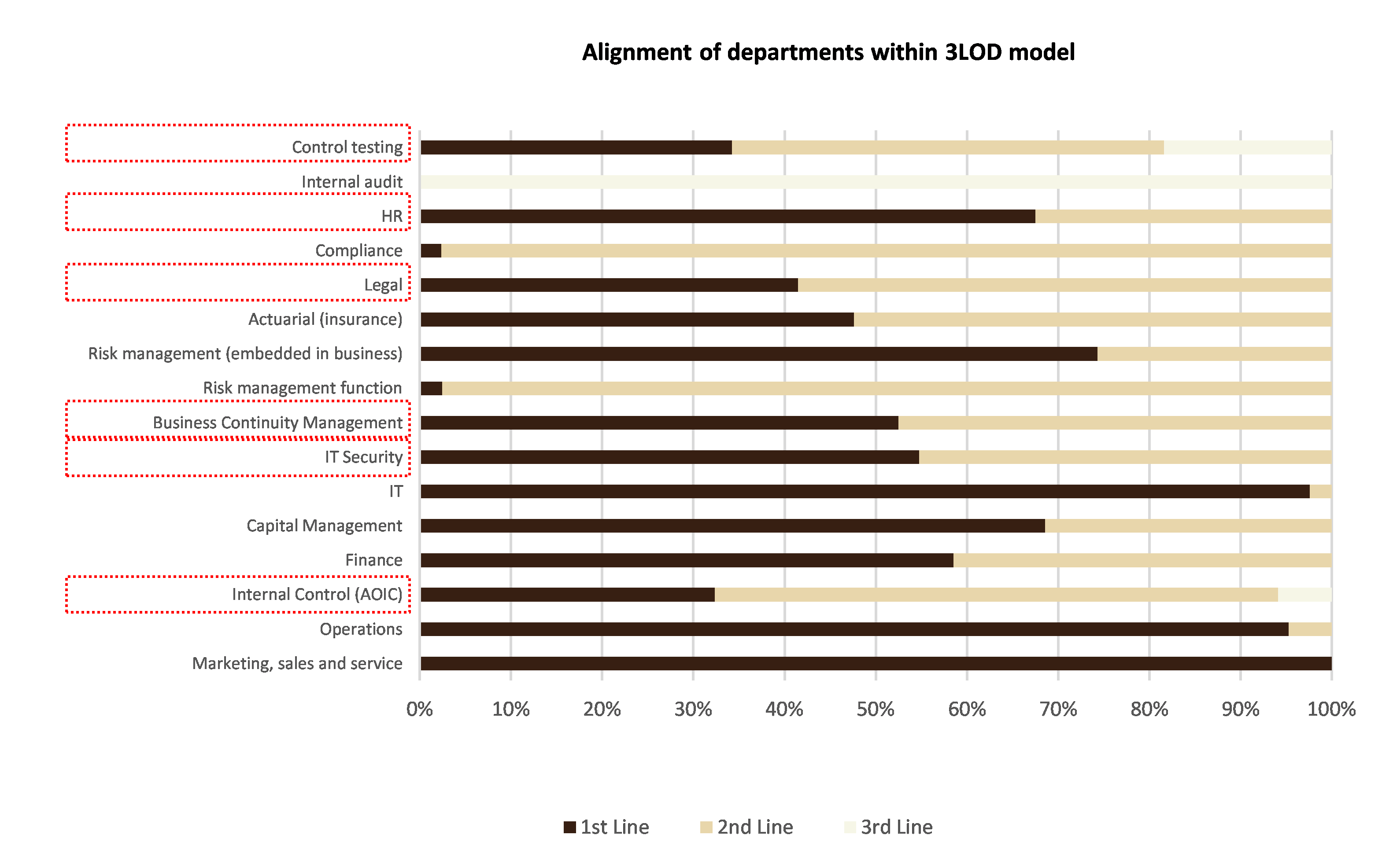

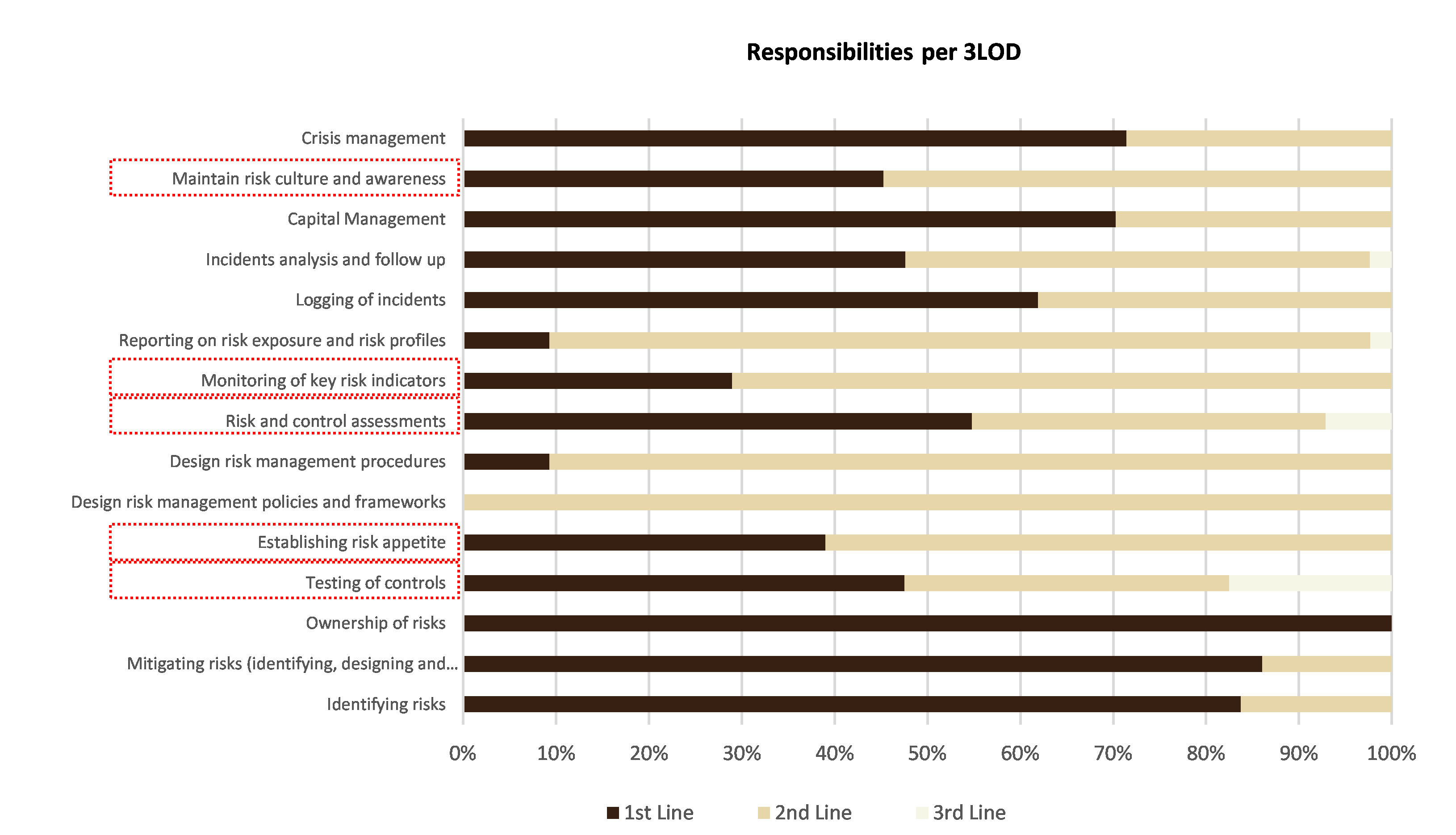

Exhibit 1: Survey findings – The allocation of activities across the three lines of defence model today has resulted in ambiguous responsibilities

It is not uncommon to observe second line functions performing first line activities such as process documentation or internal control. This can result in key second line activities not being performed at an adequate level and risks not appropriately managed. The areas causing the most confusion (see figure 3) are control testing, legal, Business Continuity Management, IT security, internal control (AO/IC), setting risk appetite, monitoring KRI’s, Risk and Control Assessments and maintaining an appropriate risk culture. IT Risk Management for example is often located in the IT organisation, despite being a key part of Operational Risk Management.

| Activities with the greatest divergence of opinion in allocation within the three lines of defence are highlighted in red. |

Figure 3: Alignment of departments and responsibilities

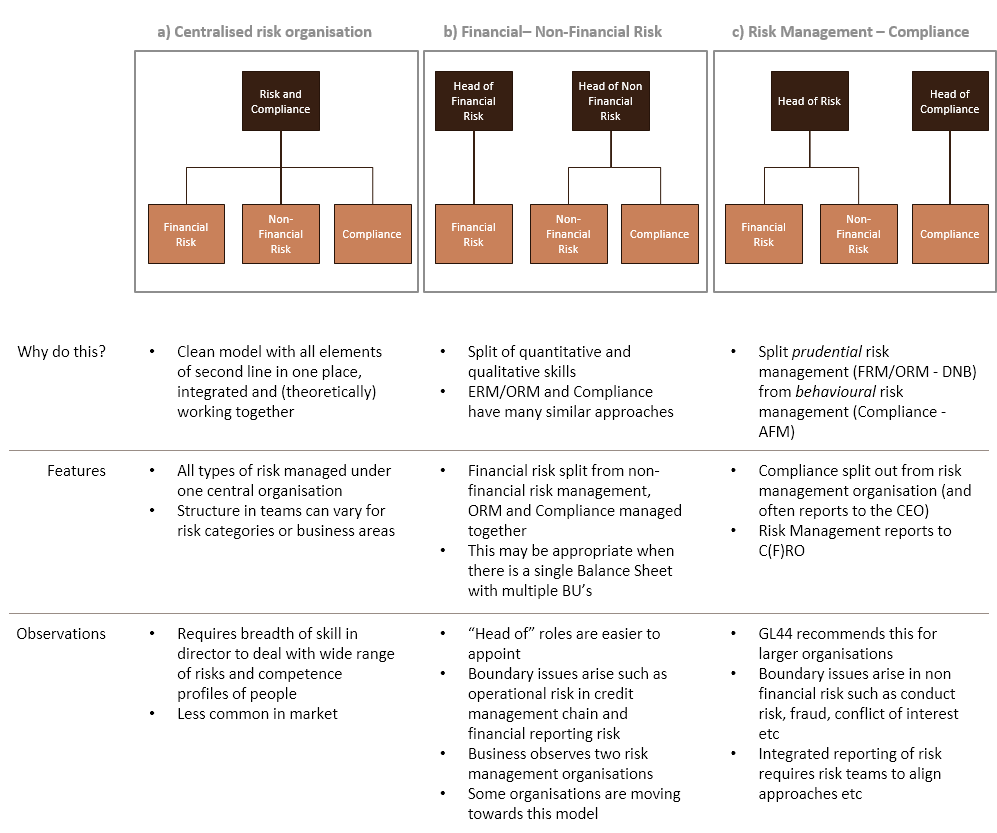

Exhibit 2: Organisational models within the second line

The effectiveness of the second line of defence is heavily influenced by the way the multiple functions and disciplines are organised. The results of our survey indicate that there are three common structures for the second line (see figure 4):

- a) Centralised risk function;

- b) Split between Financial and Non-Financial Risk Management;

- c) Compliance separate from Risk Management.

Many risk managers indicate that their model has emerged over time and is dependent upon the presence and skills of specific people. The organisation is often built around the senior risk leaders. There is no clear evidence that one model is superior to others: the better performers in our AXVECO ORM benchmark apply varying models. Each model has been accepted by regulatory authorities while the GL 44 guidelines recommend that Compliance be split out for larger institutions (model c). We have included the features of each model and reasons for organisations to adopt the models in figure 4.

Figure 4: Second line of defence organisational models and associated features

For more information see our online Risk Management eLearnings.

For any questions pleas contact Alex Dowdalls (adowdalls@axveco.com)

[i] http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32006L0048

[ii] https://www.eba.europa.eu/documents/10180/103861/EBA-BS-2011-116-final-EBA-Guidelines-on-Internal-Governance-(2)_1.pdf

[iii] https://www.eba.europa.eu/documents/10180/105241/CP44v2.pdf