Teaching the caterpillar to fly

Quite often I am being approached by clients with the following request.

“The level of risk management in our organisation needs to go up, so I think my people need training. I am looking for some basic training in – for example – risk appetite, risk identification and risk assessment?”

We should stop treating training as a solution

There is a big chance that, over the course of your career, you picked a training course (or worse: you have been sent to one) that did not lead to a change in the way you worked. Although it was enjoyable and the facilitator knowledgeable, the added value of the training to the organisation was most likely limited, questionable or not known.

Still, one of the first solutions that springs to mind to help increase the performance of a team or an organisation is send people to a training. In a way, this is not strange, since everybody has been to school and therefore grown up with the idea that training is the way to develop oneself. This has led to a still persistent belief that learning equals training and that training is the be-all and end-all to performance improvement.

I would like to plead for a more critical approach to the use of training (and more people with me (see for example Tulser 2009)), because:

- learning new skills will only create value to the organisation in specific circumstances

- the value of the training needs to expressed as results for the entire organisation

- reaping the benefits often involves a much broader set of interventions than just training

Learning itself needs to be aligned to the work environment of the professional and address his/ her development needs

Let’s look at the client question above. Yes, training can be a great way to kickstart the development of new skills or improvement of existing skills. It is good practice to use regular training, for example through e-learning, to maintain a good level of risk awareness and knowledge of basic risk management principles, i.e. the risk management foundation. Also, training can be a great way to help risk managers be better prepared for their future business environments, characterised by for example new business models, shifting risk profiles, disruptive technologies, digitisation and automation, ecosystems, platforms and agile ways of working.

What happens often in practice is that old internal risk management training material is given a good dusting down and brought back to life or standard external off-the shelf training courses are chosen. We know, however, that the effectiveness of learning is significantly increased if the learning environment closely resembles the work environment of the professional where the multiple skills also interact in a complex way (knowledge, application, behaviour, attitude). This is because the improvement opportunity presumably lies not so much in the knowledge of the risk management instruments themselves. It should instead be sought in the skills that enable professionals to apply the instruments within the context of the business and product domains, or in the soft skills that enable a risk manager to effectively and proactively challenge and advice the business on policy areas or risk appetite (e.g. through more emphasis on soft controls).

This means that the context within which one learns and applies these skills is a crucial factor for the success of the training. A training purely focused on the instruments most likely will not have a big impact on the organisation. The challenge is to define a solution that addresses the actual learning and development needs and appropriately reflects the work environment of the employees.

Learning new skills will only create value if a skills gap exists causing a lower performance

Developing (new) skills will only lead to added value to the organisation if the existing performance is too low because of the skills gap (knowledge, behaviour, attitude).

Senior management often wants a training without having done a solid investigation into the nature and root causes of the organisational performance issue: why is it that our risk management maturity level is not what it should be? Is it really caused by a shortage of skills or could there be other reasons? Consequently, there is a lack of understanding of what is needed to address the issue. This leads to a situation which is a breeding ground for unmet expectations and the training could prove to be a costly intervention.

To make it worse, external training providers tend to overestimate training outcomes and substitute these for value add to the organisation. They raise expectations of senior management who rely on the training being the solution to their problem and have a high likelihood of becoming disappointed since the effect of the training intervention will most likely be limited.

It is like teaching the caterpillar to fly.

Focus on evaluate the value to the business

Investigating the nature and root cause of the issue also provides essential input to the quantification of the value of the performance improvement opportunity. I am a strong advocate of measuring the business impact and value to the organisation for three reasons: 1) to improve the learning programme itself, 2) to maximize the transfer of learning into actual behaviours of the participants and tangible results, and 3) to demonstrate the value of training to the entire organisation.

Let us assume that a skills gap is indeed present and that this gap is a significant cause of the performance of the team or the organisation to be low. Management can then build a business case comparing the costs of doing nothing, versus the costs and the benefits of the training. Skipping this step, however difficult it might be, will lead to a situation where senior management clearly sees the costs of the proposed intervention, without having enough insight in the quantitative and qualitative benefits to the organisation. This obviously undermines sound decision making and makes it difficult, if not impossible, to steer management away from choosing the cheapest option.

Too often training is found to be “non-essential” and during cost reductions becomes one of the first programmes to be cut. Each time this has happened, one factor they have in common – the value of the programme was not evaluated at the right level.

Kirkpatrick (1994) introduced four levels of evaluating training programmes. The four steps of evaluation are:

- Step 1: Reaction – How well did the learners like the learning process?

- Step 2: Learning – What did they learn? (the extent to which the learners gain knowledge and skills)

- Step 3: Behaviour – What changes in job performance resulted from the learning process? (capability to perform the newly learned skills while on the job)

- Step 4: Results – What are the tangible results of the learning process in terms of reduced cost, improved quality, increased production, efficiency, etc.?

Often, step 1 and 2 is where the evaluation stops. We call this the happy sheet: the participants fill out an evaluation form stating they liked the training, it was fun, the trainer was knowledgeable and if they were motivated they may have learned something new. What does this tell you? It may make you feel good that the participants enjoyed the training, but there are no actual results here. Therefore, this holds little meaning unless accompanied by real results.

Step 3 and 4 are essential to demonstrate the strategic value to the organisation. Indeed, this is where you must start. If you do not know your end goal how do you know what you need to teach? Determining upfront the expected value to the organisation – i.e. the results at level 4 – is crucial to build a solid business case, to define the performance indicators to measure benefits realisation and prove the programme has impact.

When the resources, processes and values of the organisation are not aligned, even the best learning programme will not help

As soon as concrete skills with tangible benefits to the organisation have been determined a diagnostic assessment can help to identify the learning and development needs of the target population. Even if we did close the existing skills gap, however, this may not necessary lead to a higher performance, since training will not solve any other issues that may be present.

Firstly, often, multiple reasons can be identified that cause the level of risk management to be lower than desired, for example due to capacity constraints, low levels of risk awareness, lack of first line of defence ownership, ineffective processes, knowledge drain due to staff turnover, lack of clarity around roles and responsibilities etc. Some research (Deming (2000) and Rummler (2004)) even shows that approximately 80% of the organisational challenges are not caused by a shortage in skills of the employees, but due to other barriers and issues in the work environment.

Secondly, new skills need to become an integral part of the way people work and behave. This will only happen if there is ample space to put these into practice and when other barriers are removed. In other words, if the processes (ways of working, organisation, communication, etc) and values (decision making, culture, etc) do not allow employees to put the new skills into practice even the greatest learning programme will not be able to address the performance issue.

For example, one insurance company sent a group of their talented managers to a programme to boost their innovative capacity. Senior management was disappointed when nothing changed upon their return. Existing processes, structures, performance drivers and decision making were not aligned to the new way of thinking and stifled any the initiatives.

Learning is the first step in a behavioural and organisational transformation

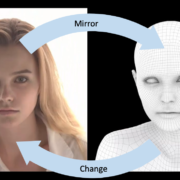

What, then, would be the best way to learn and develop these skills and how we can capture the most value of this investment? To answer this question it is important to realise that learning new skills and applying these in practice requires a fundamental change in the way we act and operate.

And changing our behaviour is very difficult.

We are often comfortable in our status quo and derive an important part of our identity – who we think we are – from what we do. If we are being asked to change the way we do things, we need to let go of a part of who we are and transition to a new – unknown – image of ourselves (a new status quo): a new identity.

This requires a structured approach with a set of interventions that follow a specific order and patience.

We generally go through several steps in a change process:

- Mindset: being open to change and having a mindset that allows oneself that things can be done differently

- Awareness: seeing how things can be or should be done differently – a vision of the new situation and what this means for us

- Intrinsic motivation: Recognising that it is worth making the transition – value to the organisation and – importantly – for yourself

- Ability: Learning new skills and having access to tools in support of the transition

- Opportunity: Applying the new skills and tools in practice and integrate them in day-to-day operations

The speed and duration of going through these steps vary per person. Skipping one or more of them may have a negative impact on the outcome or time needed for the behavioural and organisational leading to the performance enhancement.

This also means that a one-off training exercise will have limited effect. Isolated classroom based trainings are truly outdated. Learning will be more effective where the learning activities are a mix of on-the-job (online, eLearning’s, microlearning available upon request of the professional) and off-the-job (traditional formal setting). This is called blended learning and it is a great way of embedding continuous learning in your organisation what is required to solve many of today’s real life challenges.

Dominant logic and importance of mindset

The change programme will have a greater effect or will be embraced more quickly if participants themselves see that things must change. They will participate more actively if they clearly see the benefits of the transition and if these are higher than the pain of remaining in the status quo.

A key enemy of change and innovation are cultural norms; something also called dominant logic, or institutionalised thinking. It is driven by the established beliefs within organisations and acts as a blinder to peripheral vision, thereby impacting openness and receptivity to new ideas and constraining creative thinking.

We need to be aware of these established beliefs have the mindset, ability and opportunity to push ourselves to get out of our comfort zones. Senior management needs to create a positive and stimulating environment to support this transition actively demonstrating tone-at-the-top behaviour, sponsoring, coaching and aligning governance and performance management.

Combining learning and other performance improvement initiatives – a case study

In a recent project for a large Dutch bank, we developed a learning and development programme as part of a wider initiative aimed at developing their risk professionals towards becoming risk managers of the future. An important part of the learning activities were designed to increase the knowledge of disruptive technologies and their impact on the organisation’s business models and associated risk profile.

The programme was set up in a way that even the formal training consisted of 20% listening and 80% doing. The participants were asked to identify areas for improvement in their current environment, leveraging new technologies, new skills, etc. A shortlist of ideas were chosen and further developed in teams – in an agile way. The best ideas were pitched to a panel of senior business executives (Dragons’ Den), who picked a winning idea based on several criteria, including innovative character, value to the business, ease of implementation. Senior management committed budget and resources to further develop, test, refine and roll out the idea in practice.

This example shows how developing new skills through training can go hand in hand with other performance improvement initiatives, whilst a concrete opportunity is given to the professionals to put these skills into practice.

One cannot become a butterfly by remaining a caterpillar

We should stop treating training as a solution. One has to go through a process of change which involves becoming less and less of a caterpillar while becoming more and more of a butterfly. We need to recognise that any transformation process is uncomfortable and that it takes confidence, commitment and intrinsic motivation to go through the change process and actually implement something. Management needs to understand this and in order to provide the level of support needed to create a somewhat different future.

By constraining our thinking, we are limiting the potential of our people to develop, innovate and transform themselves and our organisations. Developing new skills will only create value to the organisation if a skills gap exists that causes the performance of a team or an organisation to be lower than required/ expected. Often, realising tangible results for the business involves a much broader set if interventions than just training and should be viewed as a driver of organisational transformation. Tying your training to business objectives and evaluating the real results to the entire organisation is what drives success.

I will leave you with a few questions:

- How do you determine the success of your (risk management) training?

- Did you design the training/ learning programme what the end in mind?

- What behaviours are you trying to change?

- What skills and knowledge are needed to accomplish this?

- How are you going to continue to support participants after the training is over?